Collaborative leadership and practices, the fourth pillar of community schools, provides the relational “glue” that connects and reinforces the other pillars, making it foundational and critical for the success of a community school strategy. By developing a shared vision and goals and creating participatory practices for distributing responsibilities, a community school leverages the collective expertise of all of its stakeholders. In many schools, collaborative leadership and practices are central to the work of the professionals in the building—teachers, administrators, nonteaching staff, and union leaders. Examples of this include professional learning communities, site-based teams charged with improving school policy and classroom teaching and learning, labor-management collaborations, and teacher development strategies, such as peer assistance and review.27

In community schools, collaboration and opportunities for shared leadership extend beyond staff to include students, families, community members and leaders of community-based organizations, local government agencies, and university partners. These expanded collaborations can take a range of forms, including: 1) school governance and program planning, such as responsibility for assessing school context and needs, resource distribution, and continuous improvement; 2) the coordination of services and supports; and 3) practices and systems to maintain constructive relationships between school staff and members of the community.

In **Lincoln, NE**, each community school has a School Neighborhood Advisory Council (SNAC) that includes parents, youth, neighborhood residents, educators, community-based organizations, and service providers, reflecting the diversity of the surrounding neighborhood. The SNAC assists in planning, communicating, and overseeing school programs. Each SNAC makes recommendations for specific programs and activities, and the principal and community school director work together to make final decisions.

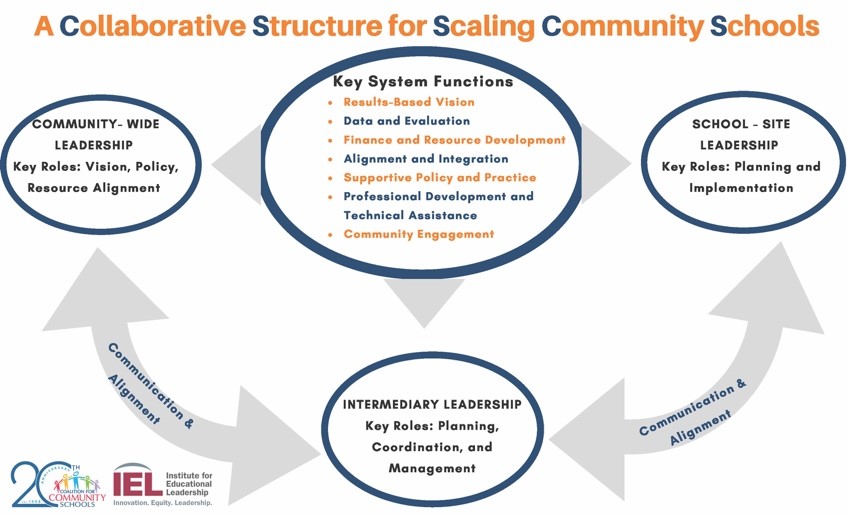

Collaboration at the district level is also central to successful implementation, especially in medium- to large-scale community school initiatives. Collaboration with families, community members, and local organizations in planning, implementation, and monitoring of initiatives pays big dividends. It improves district coordination of services and programs to best meet the needs of stakeholders, helps align communitywide goals and measures of success, and fosters strong and supportive relationships with partner organizations. For example, Multnomah County, OR, has expanded the community school strategy over the last 15 years to now include more than 80 schools in six districts. Dedicated county staff supervise and support the growth of the strategy at the system level, while nonprofit agencies, contracted and managed by the county, employ community school directors. The county has worked with nonprofit agencies to address an early childhood/school readiness component, including hiring a community schools director to support school readiness activities across their community elementary schools.

Collaborative leadership and practices help ensure that implementation is inclusive, creates shared ownership of the work, and is tailored to address local needs based on local assets. With increased leadership among families and community members, schools are better able to serve as centers of community where everyone belongs, everyone works together, and our young people succeed.28 The Coalition for Community Schools identifies collaboration among school staff, community partners, and families as a central component in its comprehensive community schools framework. It argues that collaboration is crucial to create the conditions necessary for all students to learn.29

Why Collaborative Leadership Practices?

Collaborative leadership and practices in community schools can improve school climate, strengthen relationships, and build trust and a sense of collective capacity. Trusting relationships support school transformation by helping to create nurturing and respectful environments in which caring adults, community members, and students see each other as united in working toward student success.30 The trusting and supportive relationships built through collaborative practices also extend beyond the school site and contribute to the health and safety of the broader neighborhood.

Collaborative practices enable schools and communities to work together to strengthen and expand the curriculum and activities, such as through community-led, project-based, experiential, and service learning experiences inside and outside of the classroom. Partnerships among teachers, school staff, parents, and community members can also improve school conditions that directly affect student learning, such as creating a supportive and inclusive school climate or supporting more ambitious instruction.31 Collaboration between teachers, their unions, and management that includes formal structures for shared decision making at the system level is also essential for school improvement efforts to be sustained and meaningful.32

Since 2015, the California Labor Management Initiative (CA LMI) has engaged union and district leaders to increase trust and build a sense of partnership and shared priorities. CA LMI convenes workshops, trainings, and conferences to foster strong relationships and collaborative learning among union leaders, district administrators, and school board members. Researchers linked this type of union-management collaboration to student achievement gains in six states following the same model. Schools with the highest levels of collaboration had roughly 12.5% more students performing at or above English Language Arts standards than schools with the lowest level of collaboration, when controlling for factors such as poverty, teacher experience, and school type. Additionally, high union-management collaboration rates corresponded with reduced teacher turnover, particularly in schools in high-poverty communities, with those at the top end of the collaboration distribution having similar retention rates as schools in low-poverty communities.

As educators and other school staff work with community members and families, they can make sure that the additional services and programs they provide are relevant and responsive to the needs and cultural practices of the community. Students and families, for their part, are more likely to access available resources when they have been part of the local needs and asset mapping. And, practically speaking, collaboration provides the additional human resources that schools require to offer this expanded range of activities.

Importantly, collaborative practices also extend leadership and power beyond site administrators to include teachers, school staff, parents, and community partners. By being more inclusive, these practices both improve the quality of the decisions being made and help prevent an unhealthy dynamic in which educators and other professionals see themselves as in charge of delivering services to families and communities, rather than as partners in creating a thriving school community and addressing social inequalities. Finally, collaboration can build community support for public education, including the ongoing investments that are critical to sustaining and expanding a community schools initiative.

The Need is Great and Public Support is Strong

Collaboration in community schools can help identify and address issues and resources by engaging community knowledge, addressing gaps created by structural inequity, and providing opportunities for learning in communities. Broadly, collaboration is increasingly valued as an important 21st century skill.33 With increased globalization, the need to work with people from different cultures and backgrounds to build common understanding and create solutions requires a creative and collaborative orientation.34 The collaborative practices in community schools model and nurture these skills in students and reinforce their value and impact.

Collaborative leadership and practices are increasingly recognized as supporting improvement across many diverse sectors, including nonprofits, business, and public leadership. As the world becomes increasingly more complex, diverse perspectives and knowledge are needed for all organizations to successfully improve practices and outcomes. By leveraging the leadership of all stakeholders, schools are better equipped to meet their needs and challenges.

Recent polls point to support for collaborative practices in schools. For example, a national poll conducted by the Center for American Progress found that 83% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that teachers, school districts, and states should be involved in the development of academic standards. The public also recognizes the importance of students developing these skills. In the 2017 PDK Poll, for example, 82% of respondents said they want schools to help students be cooperative and develop interpersonal skills.

Policy Principles

The following principles, derived from research and the experience of successful schools, point to key elements of state and local policy that support schools in establishing collaborative leadership and practices:

-

Require principals, teacher leaders, and superintendents to engage in collaborative goal- setting and provide relevant resources and professional development to support these practices. Stakeholders benefit from having time to assess issues, set goals, examine relevant data, and plan collaboratively. Superintendents’ collaborative goal-setting with relevant stakeholders (including central office staff, building-level administrators, and board members) is associated with improved student outcomes. Schools benefit from this broad-based input, as principals can best achieve success by enlisting the cooperation of others.35

-

Provide schools and districts with resources to support capacity-building of all stakeholders, which can result in fundamental contributions to school improvement.36 This includes opportunities and supports for collective leadership development among parents, teachers, community members, principals, and other school staff.

-

Require school leaders to establish designated times and processes for ongoing stakeholder collaboration and leadership. These can include simple measures, such as establishing regular meetings for collaborative decision making, or more complex changes, such as creating new structures and specific roles for stakeholders to help sustain participation and leadership. For example, the Community School Standards recommend creating a representative site-based leadership team, including partners, families, staff, and representation of union and school administrators, to guide collaborative planning, implementation, and oversight.

-

Require that partnerships with community organizations reflect the diversity of the community. Principals and community school directors who actively engage diverse stakeholders, facilitate stakeholder interaction, and purposefully select faculty and staff to help maintain collaborative school cultures are better able to attract beneficial partnerships and garner continued political and financial support to sustain the community school strategy.37

-

Position the community school director as a key member of the school leadership team who shares authority and responsibility with the principal for monitoring the strategy and using data to inform change and improvement. Districts should provide professional development opportunities to build the capacity for practicing shared leadership among principals and superintendents. For example, UCLA’s Principal Leadership Institute seeks to prepare educators to be social justice leaders who create democratic and culturally responsive learning environments, including building partnerships with families and community organizations.

-

Create mechanisms for systems-level collaborations between the district, city offices, community-based organizations, and other community partners to align and integrate the work of various agencies. This may include scheduling regular convenings of all the systems-level stakeholders to review community school operations, examine data, and explore areas for improvement in policy, practice, and procedures. Create Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs) between all initiative-level partners to articulate their relationships with the school district and each partner’s roles and responsibilities.

-

Ensure sufficient and sustained funding for collaborative practices to create stability and prioritize resources to high-need schools.

Policy Types and Examples

Collaborative leadership and practices should be key elements of policies establishing and supporting community schools. Already, many states and localities have integrated collaborative practices into policies consistent with a community school approach. The following examples draw from the existing policies on collaborative leadership and practices—whether stand-alone or as part of a comprehensive community school approach.

State Policies

At the state level, policy exemplars fall into three categories: 1) funding (either direct support or guidance regarding use of existing funding sources); 2) board of education resolutions; and 3) guidance regarding school improvement strategies. These policies were selected as exemplars because they include a definition of collaborative governance, attend carefully to implementation concerns, such as capacity development or the creation of physical spaces, and demonstrate a range of methods to support collaboration.

State funding and guidance

State legislation that provides funding for comprehensive community schools can include support for collaborative governance, whether it is enacted through a grant-based approach, as in Utah, or a formula-based approach enacted through the state budgeting process, as in New York. Funding mechanisms and guidance can include language to support collaboration, such as detailing the importance of convening planning teams that are broad-based and inclusive, and reinforcing that the planning itself should model the collaborative practices. Involving and aligning resources and programs from noneducational bodies such as Health and Human Services or the U.S. Department of Justice can also support and strengthen funding and guidance.

-

In Utah, the state legislature passed Senate Bill 67, establishing the Partnerships for Student Success Grant Program that dedicates $2 million to help improve schools serving low-income students by forming and sustaining community partnerships. The approach to collaboration, while not community school-oriented, is specific and includes multiple forms of collaboration on different processes and with various stakeholders. Through this grant, the state school board selects providers of leadership development trainings on a variety of topics, including building the capacity of school administrators to lead collaborative school improvement structures, such as professional learning communities. In order to be awarded a grant, each partnership must demonstrate its shared goals, outcomes, and measurement practices based on unique community needs and interests that are aligned with the state’s five- and ten-year plans to address intergenerational poverty.

-

In New York State, as outlined in Chapter 3, funds are being directed to support the implementation of community schools. This includes specific language to support collaborative practices at the school level. For example, the $75 million in funding to support the transformation of struggling schools provides that funding can be used to create a steering committee comprised of school and community stakeholders to guide and provide feedback on implementation. The funding also allows for constructing or renovating spaces within school buildings to serve a variety of purposes, including adult education spaces, resource rooms, parent/community rooms, and career and technical education classrooms. This policy is strong both because of its explicit language about collaborative practices and the intentional allocation of resources—including physical spaces—to support new forms of collaborative leadership.

State board of education resolutions

State boards of education may issue a policy or resolution in support of collaboration in community schools, as was done in West Virginia. While these resolutions tend to be shorter and less detailed than legislation, they can help in expressing a state’s support for collaborative governance and lay the groundwork for the development of more specific policy documents to follow at the state or local level. This approach does not, however, provide direct funding for community schools, which tends to be the most powerful policy lever to support meaningful change.

- The West Virginia State Community Schools Policy, adopted in 2014 by the State Board of Education, defines and provides guidance for implementing and maintaining sustainable community schools. The document specifies that: 1) community schools should strive to engage the community; 2) community school leaders must seek and act on community input; and 3) community stakeholders should be involved in both developing and implementing the vision of the school. This policy is strong because it makes a clear and compelling case for the essential role of collaborative leadership.

Local Policies

These local policies were selected as exemplars because they include a comprehensive definition of collaborative practices, place an emphasis on broad-based local input into important school site decisions, define next steps for individuals or groups responsible for implementing the strategy, and lay out clear parameters regarding effective collaboration among different groups.

-

In Alameda County, CA, a Community School Framework provides valuable support for the community school efforts in local school districts. In particular, the focus on coordination of various county agencies and departments and collaborative leadership structures at the county level—with bodies like the Alameda County Health Care Service Agency and the Office of Education—are essential for successful implementation. In its Framework, the county states that it is “guided by the core belief that it will take commitment from a broad coalition—schools and school districts, city and county departments, nonprofits, students, families, neighbors, businesses, philanthropists, and political bodies—working together to build such a network of support.” The Framework then articulates several collaborative elements and practices, including transformative leadership, capacity building, dynamic partnerships, a shared vision and goals, and the importance of schools’ connections to the surrounding community, including being accessible beyond the school day.

-

The Baltimore City Board of School Commissioners enacted a Community School Strategy that outlines the commitment of the Mayor of Baltimore and Governor of Maryland to sustain and grow the community school strategy in the city and across the state. The strategy includes language about engaging key stakeholders, developing partnerships with community organizations, providing access to school facilities, and the importance of collaboration. A district-level Community Schools Steering Committee, including key policymakers, school principals, community stakeholders, youth, funders, and advocates, creates the processes by which schools apply to become community schools, supports the community schools, and reports to the Board on progress and outcomes.

- In New York City, the Regulation of the Chancellor A-655 passed in 2010 defines a School Leadership Team (SLT) in every school. This team is responsible for developing the school’s Comprehensive Educational Plan and deciding (by consensus) if the budget and policies of the school align with the plan. This team is comprised of 10 to 17 members, including students and a Community Based Organization (CBO) representative, and must have equal numbers of parents and staff. Every school develops its own set of bylaws with some districtwide requirements in place, such as the election of parent and staff SLT members by their own constituent group in a fair manner. The district provides resources and capacity development for SLTs, such as workshops and workbooks on Making Participation Meaningful and Shared Decision Making. The SLT approach aligns well with the Community School Initiative in New York City, which was won through sustained community organizing efforts and places a strong emphasis on school-level collaborations. In each school, a lead CBO works collaboratively with the SLT and the principal to assess, plan, and carry out the community school strategy. Additionally, each community superintendent must establish a District Leadership Team, comprised of teachers, parents, and administrators, which develops the District Comprehensive Educational plan in accordance with the Chancellor’s annual goals.

- New York City’s Community School Strategic Plan lays out the plan for the city to build and sustain community schools and explains how the initiative will employ innovative and silo-breaking ways of thinking, partnering, and acting. The plan proposes a systems-building effort in which partners work to ensure a successful launch and implementation. Long-term success will also depend on the administration’s ability to establish aligned city policies that support the growth and development of community schools. To ensure effective implementation, the plan details the following roles and guiding principles:

- City Hall will ensure that city resources, partnerships, and policies will be leveraged to support community schools.

- The Office of Community Schools will ensure that there is a clear alignment across all DOE offices.

- The New York City Children’s Cabinet will coordinate the planning, policy alignment, and integration of city agencies services through ongoing collaboration, communication, and data-sharing across all 23 cabinet agencies and mayoral offices.

- The Community Schools Advisory Board will channel the expertise, energy, and ideas of outside individuals and organizations to inform policy and implementation.

Implementation

High-quality implementation is a crucial determinant of positive program outcomes. High-quality programs do not happen by chance. They result from policy choices, resource allocations, and technical assistance that support both staff capacity and student participation. They also depend on active family and community engagement, which is addressed in Chapter 5.

Characteristics of high-quality implementation

Investments in capacity-building and professional learning opportunities improve the ability of all stakeholders to collaborate and engage in a process of continuous improvement.

The national Coalition for Community Schools and partners identify standards around collaborative leadership and practices reflecting high-quality implementation, as follows:

-

Collaborative planning, implementation, and oversight are guided by a representative leadership team that includes students, families, teachers, other school staff, union representatives, principals, community school directors, community partners, and community residents. This team can exist at the school, district, or state level.

-

The leadership team plays a decision-making role in the development of the school improvement plan, working toward both academic and nonacademic outcomes.

-

Principals work with the community school directors, partners, and staff to actively integrate families and community partners into the life and work of the school.

-

At all levels of decision making, stakeholders work together to create a shared vision and mission of student success that drives educators, families, and community partners in their planning.

-

Dedicated full-time community school directors lead the site-based needs and assets assessment, facilitate alignment of school, family, and community resources; are members of school leadership teams; facilitate communication between partners; and manage data collection.

-

School personnel and community partners are organized into working teams focused on specific issues identified in the needs and assets assessment.

-

Individual student data, participant feedback, and aggregate outcomes are analyzed regularly by the site leadership team to assess program quality and progress and develop strategies for improvement.

-

A strategy is in place for continuously strengthening shared ownership for the community school among school personnel, families, and community partners.

-

School personnel, families, unions, community partners, and leaders publicly celebrate successes and advocate for community schools within their organizations and across their communities.

-

Collaborative practices at the systems level engage all initiative-level partners, including the school district, city or county officials, children’s cabinets, community partner organizations, and advocates. Partners meet regularly to discuss community school implementation, learn together based on varied experiences, and plan improvements in policies, practices, and procedures.

Endnotes

| 29 | Bryk, A. S., Sebring, P. B., Allensworth, E., Easton, J. Q., & Luppescu, S. (2010). Organizing Schools for Improvement: Lessons from Chicago. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; Gruenert, S. (2016). Correlations of collaborative school cultures with student achievement. NASSP Bulletin, 89(645), 43–55; Robinson, V., Lloyd, C., & Rowe, K. (2008). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: an analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(5), 635–74; Vescio, V., Ross, D., & Adams, A. (2008). A review of research on the impact of professional learning communities on teaching practice and student learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(1), 80–91; Kraft, M. A., & Papay, J. P. (2014). Can professional environments in schools promote teacher development? Explaining heterogeneity in returns to teaching experience. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 36(4), 476–500; Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute; Ingersoll, R., Dougherty, P, & Sirinides, P. (2017) School Leadership Counts. Philadelphia: Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania and The New Teacher Center; Rubinstein, S. A., & McCarthy, J. E. (2016). Union–Management Partnerships, Teacher Collaboration, and Student Performance. ILR Review, 69(5), 1114–1132. |

| 30 | Coalition for Community Schools (n.d.). School-community partnerships essential in a reauthorized ESEA. Washington, DC: Coalition for Community Schools_. |

| 31 | Blank, M., Melaville, A., & Shah, B. (2003). Making the difference: Research and practice in community schools. Washington, DC: Coalition for Community Schools |

| 32 | Coalition for Community Schools (2017) Community Schools: A Whole Child Framework for School Improvement. http://www.communityschools.org/assets/1/AssetManager/Community-Schools-A-Whole-Child-Approach-to-School-Improvement1.pdf |

| 33 | Sebring, P. B., Bryk, A. S., & Easton, J. Q. (2006). The Essential Supports for School Improvement. Human Development (September). |

| 34 | Rubinstein, S. A., & Mccarthy, J. E. (2012). Public school reform through union-management collaboration. Advances in Industrial and Labor Relations, 20, 1–50. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0742-6186(2012)0000020004 |

| 35 | Dede, C. (2010). Comparing frameworks for 21st century skills. 21st century skills: Rethinking how students learn, 20, 51-76. |

| 36 | Trilling, B., & Fadel, C. (2012). 21st century skills: Learning for life in our times. John Wiley & Sons. |

| 37 | Hallinger, P. (2011). Leadership for learning: Lessons for 40 years of empirical research. Journal of Educational Administration, 49(2) 125–142; For more on increasing capacity through professional learning of teachers see Robinson, V., Lloyd, C., & Rowe, K. (2008). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: an analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(5), 635–74 |

| 38 | Leithwood, K., Day, C., Sammons, P., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2006). Successful school leadership: What it is and how it influences pupil learning. Nottingham, UK: Department for Education and Skills. |

| 39 | Sanders, M. G. (2018). Crossing Boundaries: A Qualitative Exploration of Relational Leadership in Three Full-Service Community Schools. Teachers College Record, 120(4), n4. |